ISSUES

: Body Confidence

Chapter 1: Body Image

26

The ‘perfect body’ is a lie. I believed it

for a long time and let it shrink my life

As a child, Lindy West was told she was “off the charts”. In this exclusive extract from

her new book,

Shrill

, she explains how society’s fixation on thinness warps women’s

lives – and why she would rather be ‘fat’ than ‘big’.

By Lindy West

I

’ve always been a great big

person. In the months after I

was born, the doctor was so

alarmed by the circumference

of my head that she insisted my

parents bring me back, over and

over, to be weighed and measured

and held up for scrutiny next to

the “normal” babies. My head was

“off the charts”, she said. Science

literally had not produced a chart

expansive enough to account for

my monster dome. “Off the charts”

became a West family joke over

the years – I always deflected it,

saying it was because of my giant

brain – but I absorbed the message

nonetheless. I was too big, from

birth. Abnormally big. Medical-

anomaly big. Unchartably big.

There were people-sized people,

and then there was me. So, what

do you do when you’re too big, in

a world where bigness is cast not

only as aesthetically objectionable,

but also as a moral failing? You fold

yourself up like origami, you make

yourself smaller in other ways,

you take up less space with your

personality, since you can’t with

your body. You diet. You starve,

you run until you taste blood in

your throat, you count out your

almonds, you try to buy back your

humanity with pounds of flesh.

I got good at being small early on –

socially, if not physically. In public,

until I was eight, I would speak

only to my mother, and even then

only in whispers, pressing my face

into her leg. I retreated into fantasy

novels, movies, computer games

and, eventually, comedy – places

where I could feel safe, assume

any personality, fit into any space.

I preferred tracing to drawing.

Drawing was too bold an act of

creation, too presumptuous.

My dad was friends with Bob

Dorough, an old jazz guy who wrote

all the songs for

Multiplication

Rock

, an educational kids’ show

and

Schoolhouse Rock!

’s maths-

themed sibling. He’s that breezy,

froggy voice on ‘Three Is a Magic

Number’ – if you grew up in the US,

you’d recognise it. “A man and a

woman had a little baby, yes, they

did. They had three-ee-ee in the

family...” Bob signed a vinyl copy

of

Multiplication Rock

for me when

I was two or three years old. “Dear

Lindy,” it said, “get big!” I hid that

record as a teenager, afraid that

people would see the inscription

and think: “She took that a little too

seriously.”

I dislike “big” as a euphemism,

maybe because it’s the one

chosen most often by people

who mean well, who love me and

are trying to be gentle with my

feelings. I don’t want the people

who love me to avoid the reality of

my body. I don’t want them to feel

uncomfortable with its size and

shape, to tacitly endorse the idea

that fat is shameful, to pretend I’m

something I’m not out of deference

to a system that hates me. I

don’t want to be gentled, like I’m

something wild and alarming. (If

I’m going to be wild and alarming,

I’ll do it on my terms.) I don’t want

them to think I need a euphemism

at all.

“Big” is a word we use to cajole a

child: “Be a big girl!” “Act like the

big kids!” Having it applied to you

as an adult is a cloaked reminder

of what people really think, of the

way we infantilise and desexualise

fat people. Fat people are helpless

babies enslaved by their most

capricious cravings. Fat people

don’t know what’s best for them.

Fat people need to be guided and

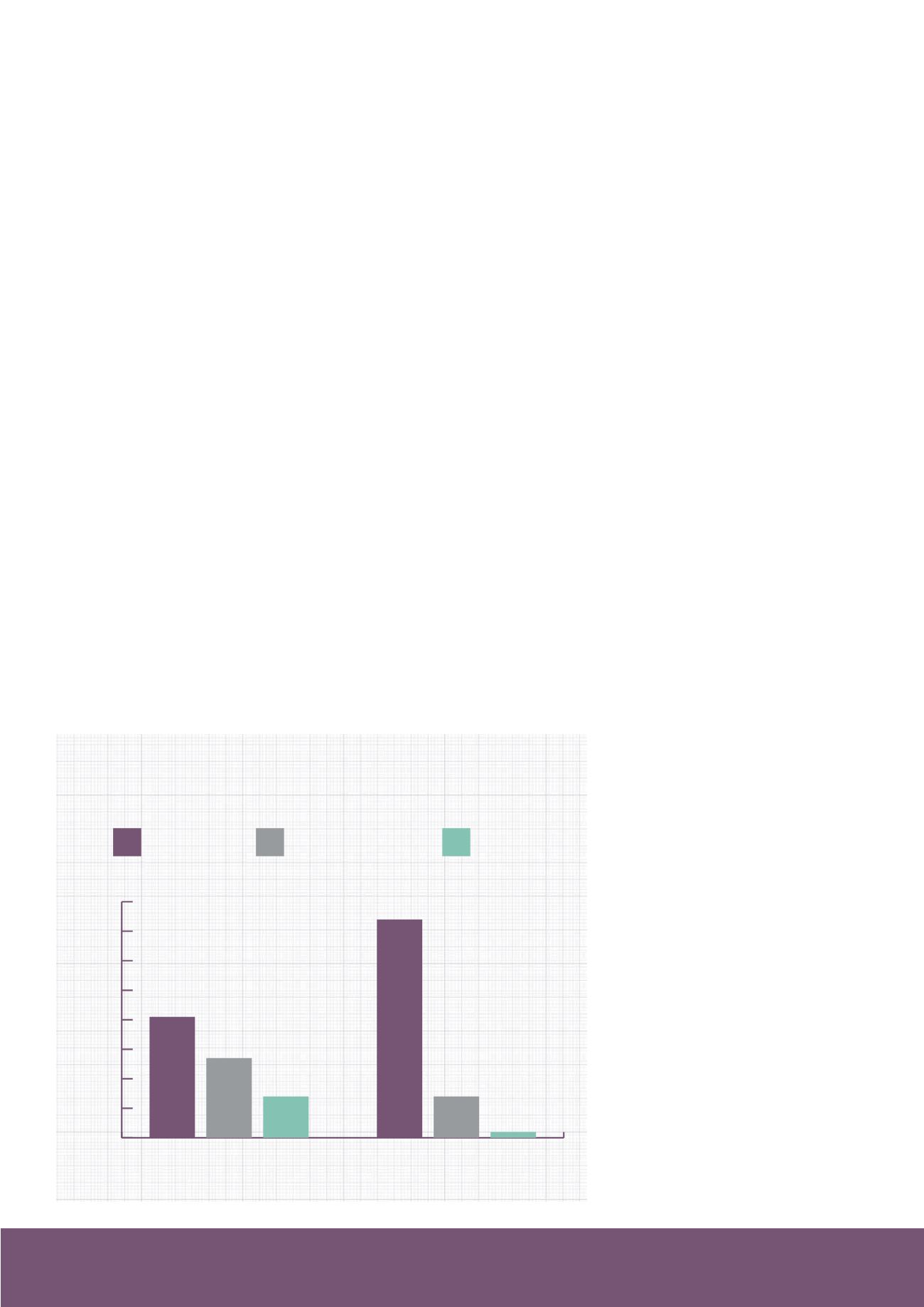

Social body pressure

Do you think that society puts too much or too little pressure on men/women

to be fit and attractive?

Source: Half of women have felt bad about their body after seeing an add, YouGov, 11 September 2015.

Too much

The right amount

Too little

Men

Women

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

41%

27%

14%

74%

14%

2%