ISSUES

: Body Confidence

Chapter 2: Self-esteem

36

To build children’s character, leave self-

esteem out of it

An article from

The Conversation

.

By Kristján Kristjánsson, Professor of Character Education and Virtue Ethics Deputy

Director, Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham

I

n the last few months the UK’s two main political

parties have entered into an apparent bidding war

over which of them can elevate the teaching of

character highest on their educational agendas before

the next general election.

With an extra flourish, the secretary of state for education,

Nicky Morgan, announced a £3.5 million fund to “place

character education on a par with academic learning” for

pupils. This money will be spent on scaling-up existing

initiatives and funding more research into character

education.

This is good news. But a more worrying feature of the

recent debate about character education is the apparent

return of self-esteem and self-confidence as virtues to

be cultivated at school.

In an article I wrote earlier this year for

The Conversation

,

I warned against the unduly restrictive focus in character

education on performance virtues, such as grit and

resilience. This is being done at the expense of other

character virtues – both moral, such as honesty and

compassion, and intellectual, such as curiosity and love

of learning. After all, who wants the resilience of the

repeat offender?

Judging from recent coverage of debates around

character education, this criticism is still valid in critiques

of the views of character expressed both by Morgan, and

Labour’s shadow education secretary, Tristram Hunt.

That said, a closer look at the full text of Morgan’s

Priestley Lecture at the University of Birmingham and

Hunt’s speech at a recent joint Demos–Jubilee Centre

conference reveals a more expansive view of character

as both steadfastly laden with values and intrinsically

important for a well-rounded, flourishing life.

Consciously building character

Some red herrings still survive in these waters. The terms

“soft” and “non-cognitive” skills are relentlessly swirled

around as designators of character virtues, at least of

the performance kind. I hope this is just a language issue

– politicians and journalists share a love of short and

catchy phrases – because from an academic standpoint

both terms are terrible misnomers.

Character traits are notoriously resistant to change, at

least after middle to late childhood. There is a lot of truth

in the words of Nobel Prize Laureate J M Coetzee that,

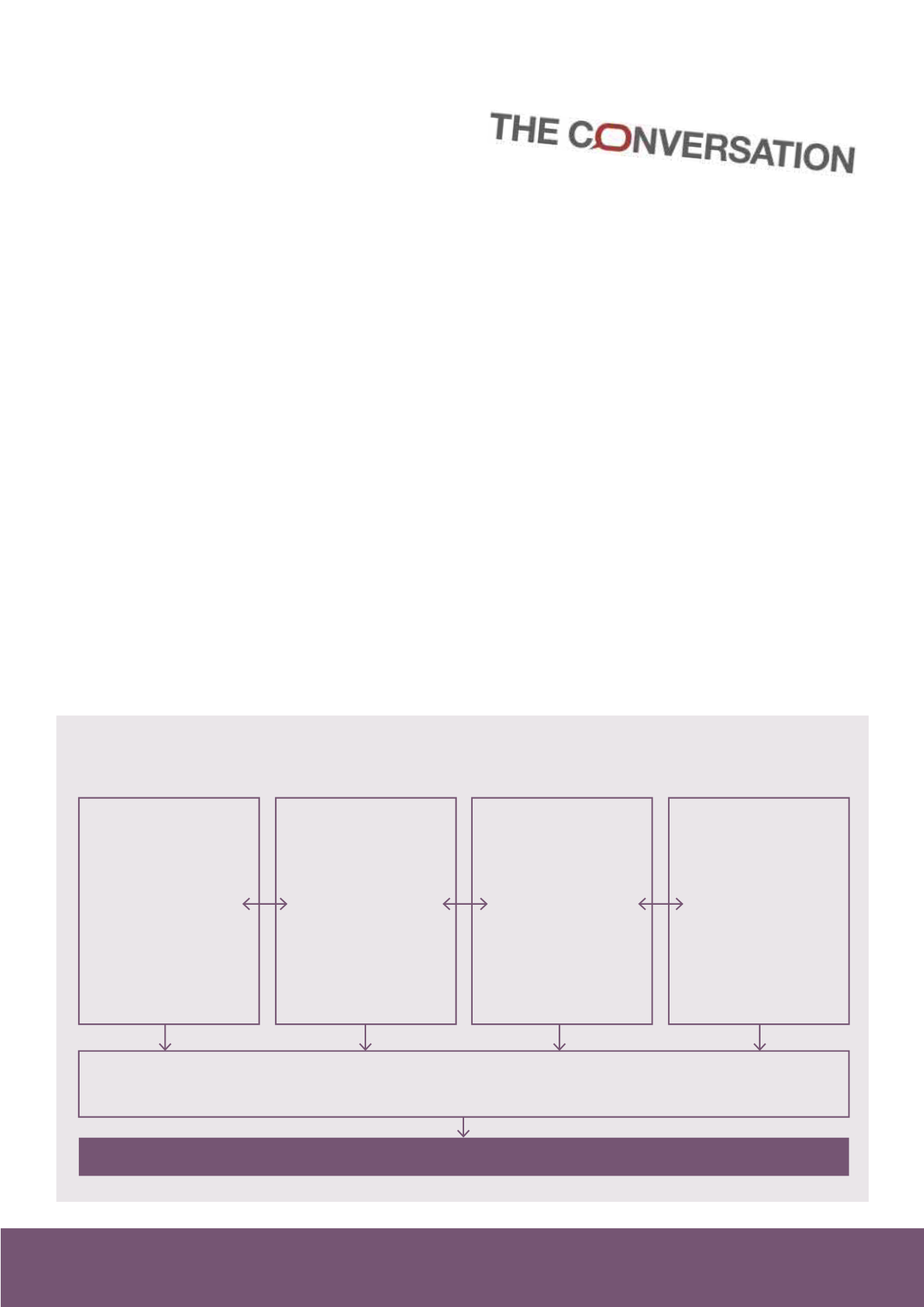

What is character education?

Source: A framework for chararcter education in schools, Jubilee Centre, Accessed 12 September 2016.

‘[...] the ultimate aim of character education is the development of good sense or practical wisdom: the capacity to choose

intelligently between alternatives.’

Moral virtues

Those which enable us

to respond well to

situations in any area

of experience.

Examples: courage;

compassion for others;

gratitude; justice; honesty;

humility/modesty;

self-discipline; tolerance;

respect; integrity.

Civic virtues

Those necessary for

engaged and

responsible citizenship.

Examples: service;

neighbourliness, citizenship;

community awareness and

spirit; volunteering; social

justice.

Performance virtues

Behavioural skills and

psychological

capacities that enable

us to put the other

virtues into practice.

Examples: resilience,

perseverance, grit and

determination; leadership;

teamwork; motivation/

ambition; confidence.

Intellectual virtues

Those required for the

pursuit of knowledge,

truth and

understanding.

Examples: reflection; focus;

critical thinking, reason and

judgement; curiosity;

communication;

resourcefulness;

openmindedness.

Flourishing individuals and society

Practical Wisdom / Good Sense / Phronesis

Knowing what to want when the demands of two or more virtues collides.